Afastamento ilegal

Leia a decisão da OIT favorável a José Maurício Bustani.

Da Redação

terça-feira, 29 de julho de 2003

Atualizado às 08:11

Afastamento ilegal

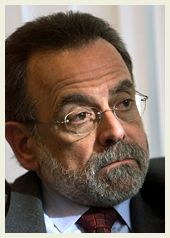

O Tribunal Administrativo da Organização Internacional do Trabalho considerou ilegal o afastamento do ex-secretário-geral da Organização para a Proscrição de Armas Químicas, o embaixador brasileiro José Maurício Bustani. Além da ilegalidade o Tribunal decidiu que a Organização deve pagar multa de 50 mil Euros para compensação de danos morais e mais cinco mil Euros de custos.

O Tribunal levou em consideração a alegação de que a maneira como Bustani foi demitido teve motivações políticas e não administrativas como prevê o regulamento da OIT.

"De acordo com a lei estabelecida em todos os tribunais administrativos internacionais, o tribunal reafirma que a independência de empregados civis internacionais é uma garantia essencial, não somente para os empregados civis eles mesmos, mas também para o funcionamento apropriado de organizações internacionais. [...] Concede que a autoridade em que o poder da nomeação é investido - neste caso a conferência dos partidos dos Estados da organização - seu afastamento constituiria uma violação inaceitável dos princípios em que as atividades das organizações internacionais são fundadas, rendendo oficiais vulneráveis às pressões e à mudança política. [...] O reclamante não teve nenhuma garantia processual, e dado às circunstâncias de seu caso, tem embasamento para afirmar que a terminação prematura de sua nomeação viola os termos de seu contrato de emprego e contraria os princípios gerais da lei do serviço civil internacional". (Texto do Tribunal).

No relatório o Tribunal explica que:

No relatório o Tribunal explica que:

"O autor da ação alega a ruptura de seus direitos contratuais. Embora seu contrato fornecesse para sua possibilidade para renunciar, não estipulou nenhum direito da organização terminar seu contrato antes de seu prazo final. Além, sua nomeação foi renovada unanimemente um ano antes que esteve ajustada para expirar inicialmente. Última, diz que a razão dada para seu afastamento era uma mera referência à" falta da confiança "; considera este ser extremamente vago e subjetivo. Fornece o tribunal com o que acredita para ser a motivação real atrás de seu afastamento. Alega que a conferência não agiu no mais melhor interesse da organização, mas curvado à pressão política". (Texto do Tribunal).

O afastamento de Bustani foi requisitado pelos Estados Unidos da América.

____________________

|

| ||

|

Judgment No. 2232 | ||

|

The Administrative Tribunal, | ||

Considering the complaint filed by Mr J.M. B. against the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) on 19 July 2002 and corrected on 26 August, the OPCW's reply of 29 November 2002, the complainant's rejoinder of 28 February 2003, and the Organisation's surrejoinder of 31 March 2003;

Considering Articles II, paragraph 5, and VII of the Statute of the Tribunal;

Having examined the written submissions and decided not to order hearings, for which neither party has applied;

Considering that the facts of the case and the pleadings may be summed up as follows:

A. The complainant, a Brazilian national born in 1945, is a former Director-General of the OPCW.

He was appointed, for a period of four years, as Director-General on 13 May 1997 by the Conference of the States Parties upon recommendation of the Executive Council. On 19 May 2000, one year before the end of his term, the Conference of the States Parties decided, again upon a recommendation of the Executive Council, to renew his contract for a further four years.

On 21 March 2002, at the 28th Session of the Executive Council, a no-confidence motion, calling for the complainant to resign as Director-General, was introduced by a State Party (the United States of America). The motion failed. A special session of the Conference of the States Parties was subsequently called for by the same State Party and at its meeting of 22 April 2002 the Conference adopted a decision to terminate the appointment of the Director-General effective immediately. That is the impugned decision.

B. The complainant argues in the first place that the necessary conditions for the Tribunal to be competent to hear his complaint have been fulfilled. The decision affects his interests, it is a final one, and it has been taken by the highest authority of the Organisation. In addition, it is a quasi-administrative decision that cannot be appealed in the manner prescribed by the Staff Regulations and Interim Staff Rules. He submits that as there was simply no reasonable way of applying an internal remedy to his case, and no recourse to internal or other procedures being open to him, he could come directly to the Tribunal. In support of his argument he gives his interpretation of Staff Rule 11.3.01,concerning the right of appeal to the Tribunal. He asserts that, the OPCW having formally accepted the jurisdiction of the Tribunal for all disputes between the Organisation and its personnel, the jurisdiction can and must be extended to hear his case. Otherwise, he would be "deprived of access to any forum, judge, effective jurisdiction or legal protection".

On the merits, the complainant asserts that the decision of 22 April 2002 terminating his contract was illegal. He contends, firstly, that the Special Session of the Conference of the States Parties was not convened in conformity with the rules of procedure. Being procedurally flawed, the decision must be declared null and void. Secondly, the decision lacked a valid legal basis. The Conference may only take decisions within the powers and functions bestowed upon it by the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction (hereinafter the "Chemical Weapons Convention"). That instrument gives the Conference the authority to appoint the Director-General or renew his term; it does not give the Conference the authority to dismiss him. He says it is reasonable to conclude that the absence of such a provision means that the authors of the Convention did not intend to make it possible for a director-general to be removed during his term, absent a criminal or quasi-criminal offence. Therefore, the Conference is bound by its two earlier decisions, the one initially appointing him and the second one renewing his mandate.

Furthermore, he asserts that the decision was taken by an incompetent authority. The matter of dismissing him was first brought before the Executive Council by a State Party. However, that body had rejected the no-confidence motion brought before it. It was the same State Party which then requested the convening of a special session of the Conference of the States Parties, but the procedure was not correctly followed. In any case, the Conference is not an appeals body in respect of decisions taken by the Executive Council and it has been "abusively and erroneously seized" of the matter.

The complainant pleads breach of his contractual rights. Although his contract provided for his possibility to resign, it did not stipulate any right of the Organisation to terminate his contract before its expiry. In addition, his appointment had been unanimously renewed one year before it was set to initially expire. Lastly, he says that the reason given for his dismissal was a mere reference to "lack of confidence"; he considers this to be extremely vague and subjective. He provides the Tribunal with what he believes to be the real motivation behind his dismissal. He alleges that the Conference did not act in the best interest of the Organisation but rather bowed to political pressure.

He requests the Tribunal to quash the decision of the Conference of the States Parties terminating his appointment as Director-General of the OPCW. He claims, as material damages, payment of the salary, indemnities and allocations owed to him for a period of three years and three weeks. He also claims compensation for the "enormous pain, anguish and suffering" the decision caused him. He evaluates the moral injury at one million euros, which he intends to pay to the Organisation for the exclusive use of funding the activities of the Programme of International Cooperation - Technical Assistance to Developing Countries should the Tribunal decide to grant him that compensation. Lastly, he claims reimbursement of all the fees and expenses related to lodging his complaint.

C. In its reply the OPCW contests that the Tribunal is competent to hear the complaint. First, the complainant failed to demonstrate that the decision taken by the Conference of the States Parties on 22 April 2002 constituted non-observance of the terms of his appointment or of the provisions of the Staff Regulations. Secondly, as Director-General of the OPCW, the complainant was not subject to either the Staff Regulations or the Interim Staff Rules. Consequently, Article II, paragraph 5, of the Tribunal's Statute has not been complied with. In addition, it is clear that neither the complainant's letter of appointment nor his letter of renewal designate the Tribunal as the competent body to settle any disputes regarding the interpretation or application of his contract of employment with the Organisation. The OPCW refers to another international organisation which has specifically provided that the Tribunal is competent to hear disputes concerning that organisation and its executive head; it points out that the OPCW has not done so. It contends that in its case law the Tribunal has held that the choice of forum for resolving disputes may not be implied but must be expressly agreed to by the parties. Lastly, it argues that the Organisation's Staff Regulations provide for recourse to the Tribunal only against administrative decisions. However, the decision taken by the Conference of the States Parties is not an administrative decision but rather a political one.

Regarding the complainant's allegation that he would have no other forum for resolving this dispute if the Tribunal were to decline jurisdiction, the OPCW points out that the complainant could have resorted to negotiations, the use of third party's good offices, or even arbitration. He has made no attempts to avail himself of any of these possibilities. It brings to the Tribunal's attention that even the complainant himself has conceded that the Interim Staff Rules do not offer a sufficient legal basis for challenging the legality of the impugned decision.

On the merits, it denies that the Special Session of the Conference of the States Parties was not legally convened and that a particular State Party was solely and exclusively responsible for the termination of his contract. It argues that lack of confidence constitutes an exceptional circumstance, thus it was a legitimate reason for terminating the complainant's contract. Lack of confidence in a director-general puts in jeopardy "the preservation and effective functioning of the Organisation". It submits that the Chemical Weapons Convention provided legal grounds for ending his appointment. Likewise, the Conference of the States Parties was competent to take a decision on this matter. The main issue before the Executive Council had been an invitation for the Director-General to resign. But the issue before the Conference was the termination of his contract; it was not, therefore, being used as an appeals body for an Executive Council decision. It submits that the reason his re-election had been supported one year before the end of his mandate was because there was no alternative candidate.

It denies that the complainant's contractual rights have been breached.

D. In his rejoinder the complainant presses his pleas regarding receivability and the competence of the Tribunal. He argues that he is indeed an "official" of the OPCW; this is clear from the terms of the Headquarters Agreement between the Organisation and the Kingdom of the Netherlands according to which "[o]fficials of the OPCW" means the Director-General and all members of the staff of the Technical Secretariat. In addition, his contract of employment makes it clear that he was to receive his benefits and entitlements in accordance with the Staff Regulations and Interim Staff Rules. Consequently, the Tribunal is competent to hear his complaint, just like that of any other staff member of the OPCW. He contends that decisions regarding the appointment of a director-general are "administrative" despite being taken by the Conference of the States Parties, a political organ, because these are taken in its capacity as an appointing authority.

He accuses the Organisation of presenting the facts in a misleading manner; he provides his own interpretation. Pointing out that he had been "unanimously" re-elected one year before his first term ended, with comments praising his performance, he calls into question the OPCW's assertion that this was because there was no alternative candidate. He submits that one year would have been sufficient for identifying a suitable alternative; in fact, his replacement was found in only two months.

He submits that neither the Chemical Weapons Convention nor the Rules of Procedure of either the Executive Council or the Conference of the States Parties provide for a no-confidence motion. Even if there had been grounds for his removal, the principles of due process and natural justice would have required that he be informed of the allegations against him and given the opportunity to respond to them. He maintains that the decision to dismiss him infringed his contractual rights and that he was not given reasons for it. Also, the Organisation has failed to rebut his arguments on the substance of his complaint.

He considers the Organisation's claim of "lack of confidence" in him to be a very serious accusation which should be used only when the accused has manifestly exhibited behaviour so unacceptable that one can no longer rely on that person to carry out his duties. Being very vague this accusation must be accompanied by references to specific acts attributed to the accused. The OPCW has failed to do so in his case; consequently, he has been deprived of his right to due process. Furthermore, the Organisation has not indicated which legal text provides for lack of confidence as a valid ground for the Conference of the States Parties to terminate his appointment. He reiterates that the Conference was not competent to take the decision, at least not in the absence of a prior recommendation from the Executive Council. If, as the Organisation has said in its reply, the decision proposed to the Executive Council was meant as an "invitation" for him to resign voluntarily, then it cannot have constituted a "recommendation" from that body to the Conference to dismiss him.

E. In its surrejoinder the OPCW maintains its version of the facts. Regarding the competence of the Tribunal and the receivability of the complaint, it presses its pleas that the decision to terminate the complainant's appointment was a political one, therefore the Tribunal is not competent to entertain the complaint. Nor is it competent to rule on the legality of the decision of the Conference of the States Parties of the OPCW. Furthermore, it points out that the Interim Staff Rules are applicable only to "staff members appointed by the Director-General". It "follows logically" that the Director-General cannot avail himself of the staff rule giving staff members the right to appeal to the Tribunal. That the Director-General is not a staff member is also clear from Staff Regulation 1.2, which provides, in part, that staff members "are subject to the authority of the Director-General". The fact that the complainant was considered an official of the OPCW under the terms of the Headquarters Agreement has no relevance insofar as whether the terms of his appointment provided for the competence of the Tribunal in the event of a dispute regarding his contract of appointment.

On the merits, the Organisation denies the complainant's allegations and it presses its pleas.

1. Under the terms of Article VIII, paragraph 4, of the Convention establishing the OPCW, the organs of the Organisation are "the Conference of the States Parties, the Executive Council, and the Technical Secretariat". According to paragraph 41 of that same Article:

"The Technical Secretariat shall comprise a Director-General, who shall be its head and chief administrative officer, inspectors and such scientific, technical and other personnel as may be required."

Paragraph 43 reads as follows:

"The Director-General shall be appointed by the Conference upon the recommendation of the Executive Council for a term of four years, renewable for one further term, but not thereafter."

2. Pursuant to those provisions and to paragraph 21(d) of Article VIII, which provides that the Conference of the States Parties shall "[a]ppoint the Director-General of the Technical Secretariat", the Conference appointed the complainant as Director-General for a four-year term by a decision of 13 May 1997. It decided on 19 May 2000 to renew that appointment for another four-year term, which began on 13 May 2001 and was due to end on 12 May 2005. By that same decision, the Conference authorised its Chairman to sign a contract with the Director-General, incorporating terms and conditions already stipulated in an Executive Council decision of 30 January 1998. On 23 February 2001 an exchange of letters between the Chairman of the Conference and the Director-General formalised the renewal of the latter's term.

3. The Organisation points out in its submissions that at the time when the renewal was decided certain Member States already had reservations as to the Director-General's management style, and that they had accepted the renewal of his term only in the absence of an alternative candidate and in the hope that he would improve his performance, but this hope did not materialise.

These "reservations" did not prevent the complainant from obtaining a unanimous vote "by acclamation". Nevertheless, the Director-General's management was subsequently called into question and in March 2002 a Member State, namely the United States of America, which is a major contributor to the funding of the Organisation, submitted a no-confidence motion to the Executive Council, inviting the Director-General to inform the States Parties that he would resign from his functions no later than 31 March 2002. This motion was supported by 17 members, but five voted against it and 18 abstained. The two-thirds majority of all Executive Council Members required for decisions on "matters of substance" was not reached and the motion was therefore not adopted. However, the same Member State, whose hope that the Director-General would leave of his own accord following that vote proved in vain, called for the convening of a special session of the Conference of the States Parties with an agenda which was to include a "[d]ecision related to the tenure of the current Director-General of the Technical Secretariat". The Director-General responded to the allegations against him, but on 22 April 2002, by a majority of 48 votes in favour, with 7 against and 43 abstentions (2 States Parties being absent), the Conference took the decision to terminate the complainant's appointment with immediate effect. The majority of the Conference thereby intended to underline its determination "to work for the preservation and effective functioning of the Organization and the Convention, which [were] put in jeopardy by the lack of confidence in the present Director-General of the Technical Secretariat".

4. Having thus been removed from office, the complainant filed a complaint on 19 July 2002 asking the Tribunal to set aside the decision to terminate his appointment and to order the Organisation to pay him damages in respect of the material and moral injury which it has caused him.

5. The Organisation replies that the Tribunal lacks jurisdiction to hear his case and raises several objections to receivability.

6. On the issue of jurisdiction the Organisation recalls that, by a letter of the Director-General dated 2 July 1997, it has accepted the Tribunal's jurisdiction to hear complaints concerning non-observance of the terms of appointment of staff members, and of such provisions of the Staff Regulations as are applicable. The relevant Staff Regulations provide:

"Regulation 11.1:

Staff members have the right of appeal against any administrative decision alleging non-observance of the terms of appointment, including relevant Staff Regulations and Rules, and against disciplinary action."

"Regulation 11.3

Arrangements shall be made for the hearing by the Administrative Tribunal of the International Labour Organisation of appeals by staff members against the administrative decisions referred to in Staff Regulation 11.1. These arrangements shall fully respect the Annex on the Protection of Confidential Information of the Convention and the OPCW Policy on Confidentiality."

According to the defendant, the complainant was not a "staff member" within the meaning of those provisions, and the decision he impugns is not an administrative decision, but a political decision taken in a political context by the highest legislative and political body of the Organisation. The complainant asserts, on the contrary, that the Tribunal's jurisdiction is determined by Article II, paragraph 5, of its Statute, which provides as follows:

"The Tribunal shall also be competent to hear complaints alleging non-observance, in substance or in form, of the terms of appointment of officials and of provisions of the Staff Regulations of any other international organization meeting the standards set out in the Annex hereto which has addressed to the Director-General a declaration recognizing, in accordance with its Constitution or internal administrative rules, the jurisdiction of the Tribunal for this purpose, as well as its Rules of Procedure, and which is approved by the Governing Body."

The complainant argues that he was indeed an "official" of the Organisation, appealing against a breach of his contractual rights. He asserts that his complaint can be heard by the Tribunal since the defendant has recognised its jurisdiction.

7. The first issue to be resolved is that of whether the complainant is an "official" within the meaning of the Statute of the Tribunal, and a "staff member" for the purposes of the Organisation's submission to the Tribunal's jurisdiction. There is no doubt that the complainant was an "official" within the meaning of the Statute of the Tribunal. In his capacity as head of the Technical Secretariat he was in fact the foremost "official" of the Organisation. Indeed, the Headquarters Agreement between the Organisation and the Kingdom of the Netherlands specifically defines "officials" of the OPCW as including "the Director-General and all members of the staff of the Technical Secretariat of the OPCW, except those who are locally recruited and remunerated on an hourly basis". Although, as the defendant rightly points out, the terms of the Headquarters Agreement have no effect on the Tribunal's jurisdiction, the fact remains that at the time when that Agreement was signed, the word "officials", in standard usage, was considered by the Organisation to include the Director-General. The Tribunal must hold that, in accordance with the provisions of its Statute, its jurisdiction does, in principle, extend to disputes concerning that "official".

8. However, that jurisdiction must not be excluded either by the Organisation's submission to the Tribunal's jurisdiction or by its own statutory provisions. In this connection, the submission to jurisdiction refers to "complaints alleging non-observance, in substance or in form, of the terms of the appointment of staff" and the relevant provisions of the Organisation's Staff Regulations confer a right of appeal on "staff members". The defendant argues that this category excludes the Director-General on the following grounds: Staff Regulation 1.2 expressly provides that staff members are subject to the authority of the Director-General and responsible to him in the exercise of their functions, whilst the Staff Rules - established by him - apply to "staff members appointed by the Director-General", as provided by Staff Rule 0.0.1, which would exclude the Director-General himself. The Tribunal cannot accept that view: the Director-General, as head of the Technical Secretariat, is appointed by decision of the competent authority which establishes his conditions of remuneration and defines the benefits to which he, like other senior-ranking staff members of the Technical Secretariat, is entitled pursuant to the Organisation's Staff Regulations and Interim Staff Rules. Moreover, Article VIII, paragraph 46, of the Chemical Weapons Convention provides that:

"In the performance of their duties, the Director-General, the inspectors and the other members of the staff shall not seek or receive instructions from any Government or from any other source external to the Organization. They shall refrain from any action that might reflect on their positions as international officers responsible only to the Conference and the Executive Council."

Thus, the Director-General, like other staff members, is clearly deemed to have the status of an international civil servant. Consequently, the Director-General must be regarded as a staff member both for the purposes of the Organisation's submission to the Tribunal's jurisdiction and Staff Rule 11.3.01(a).

9. The defendant nevertheless considers that since the particular case of the Director-General of the Organisation was not expressly provided for in the texts on which the Tribunal's jurisdiction is based, an express provision recognising its jurisdiction would have been necessary. It points out that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), having realised that it had no statutory provision nor any contractual stipulation attributing jurisdiction in the event of a dispute involving its Director-General, decided in 1999 to include such a clause in the contract it signed with him. Whilst the Tribunal does not deny that UNESCO thereby clarified difficulties which were liable to arise, it does not view that as authority for the reverse proposition that contracts containing no such clause, entered into by other organisations with their respective chief administrative officers, must be deemed to exclude the jurisdiction of the Tribunal.

Admittedly, the Tribunal held in Judgment 967, under 5, to which the defendant refers , that "[t]he choice of the Tribunal as the forum in cases in which it would not otherwise have jurisdiction is a term which by its very nature may not be implied but must be expressly agreed between the parties"; and in Judgment 605, under 7, that "the Tribunal has no more than the competence conferred on it" and "is bound by the provisions of its Statute", which determine its jurisdiction. However, in the present case, the provisions of the Statute of the Tribunal, combined with the declaration recognising the Tribunal's jurisdiction to hear disputes "between the Organisation and its employees", in no sense excludes the Tribunal's jurisdiction to rule on a complaint filed by the former Director-General and concerning the duration of his appointment. Although the procedural rules governing appeals by staff members to the Tribunal do not appear to be appropriate to the case of the Director-General, as will be discussed under 13, that weakness cannot deprive him of his right, as an international civil servant, to come before the Tribunal.

10. Thus, the Tribunal's jurisdiction ratione personae is established. But what of its jurisdiction ratione materiae? The defendant contests it, arguing that the decision impugned before the Tribunal is not an administrative decision, but essentially a political one. Staff Regulations 11.1 and 11.3 provide that staff members are entitled to challenge "administrative decisions" contravening the terms of their appointment. The Organisation refers to Judgment 209, in which the Tribunal held that it lacked jurisdiction to rule on the legality of a resolution adopted by the Plenipotentiary Conference of the International Telecommunication Union, the Union's "legislative organ". That ruling is clearly not applicable to the present case: a decision terminating the appointment of an international civil servant prior to the expiry of his/her term of office is an administrative decision, even if it is based on political considerations. The fact that it emanates from the Organisation's highest decision-making body cannot exempt it from the necessary review applying to all individual decisions which are alleged to be in breach of the terms of an appointment or contract, or of statutory provisions.

11. The defendant raises several objections to receivability. It considers that the complaint is irreceivable ratione personae, because the former Director-General does not have locus standi to bring his case before the Tribunal, and also ratione materiae, in that the impugned decision is not an administrative decision of the kind which may be referred to the Tribunal. Furthermore, it argues, the applicable statutory provisions stipulate that before a dispute can be referred to the Tribunal, it must first be examined by the Appeals Council, which is competent to hear appeals by staff members against administrative decisions concerning them, and this procedure was plainly inconceivable in the case of an appeal by the former Director-General.

12. The first two objections to receivability have been sufficiently addressed in the foregoing discussion on the Tribunal's jurisdiction: the complainant was an international civil servant who was entitled to appeal to the Tribunal against a decision to terminate his appointment. That decision must be viewed as an administrative decision, even though it was taken by the Conference of the States Parties.

13. The third objection to receivability raises a more delicate issue. Staff Rule 11.3.01(a) provides that staff members can appeal to the Tribunal against administrative decisions and disciplinary actions taken after reference to the Appeals Council, which implies that the provisions governing the composition and procedural rules of the Appeals Council must also be taken into account. In the present case, that procedure was not and clearly could not have been followed. Indeed, it is hard to imagine how the Director-General, stripped of his functions, could have appealed to the Appeals Council established under his own authority, against a decision of the Conference of the States Parties, with a view to obtaining a final decision by the new Director-General. The defendant rightly submits that this procedure is entirely inappropriate, which the complainant accepts. However, the fact that these rules are unsuitable cannot have the effect of depriving an international civil servant of the right to have his complaint examined by a judicial body. An appeal to the Appeals Council was inconceivable, and the impugned decision was clearly a final decision - within the meaning of Article VII of the Tribunal's Statute - that only the Conference of the States Parties itself could have quashed, which could not be envisaged under the circumstances. In that situation, a direct appeal to the Tribunal - which Staff Rule 11.3.01(b) in fact permits - was clearly the only remedy available to the complainant. The complaint must therefore be considered receivable.

14. On the merits, the complainant puts forward several grounds for setting aside the impugned decision: he argues that the decision was taken following a flawed procedure, because the convening of the Special Session of the Conference of the States Parties contravened the Conference's Rules of Procedure; that it was taken by a non-competent authority and lacks both a valid legal basis and sufficient motivation; that it violated his contractual rights; and that it amounted to misuse of authority, having been taken under pressure from one of the States Parties, the United States of America, which had threatened to withhold its financial contributions to the Organisation were the Director-General to remain in office.

15. At the insistent request of the United States, the Conference of the States Parties felt bound to terminate the complainant's appointment, despite the fact that it had been renewed by acclamation less than two years prior to the no-confidence motion presented to the Executive Council in circumstances which are described under A above. The evidence on file and the applicable texts indicate that although the convening of the Special Session of the Conference of the States Parties was procedurally correct, and although the Conference does indeed have a broad competence, under Article VIII, paragraphs 19 and 21, of the Convention, to examine all problems lying within the scope of the Convention, "including those relating to the powers and functions of the Executive Council and the Technical Secretariat", and to appoint the Director-General, the reasons put forward in announcing what can only be described as the dismissal of the Director-General were extremely vague. Admittedly, the Permanent Representative of the United States to the OPCW had informed the Director-General, on 28 February 2002, of his Government's criticisms regarding the Director-General's management, and had asked him to resign. The "concerns" entertained by the United States were expressed in a paper published on 1 April 2002 by the US Department of State, and some of its grievances were highlighted by the US Permanent Representative in his statement to the Special Session of the Conference of the States Parties: poor financial management, abdication of transparency, destruction of staff morale, negligence and, in general, betrayal of the trust placed in him by the States Parties. It was on the basis of those charges, to which the complainant responded, that the Conference took its decision, and it may be assumed that the majority of its Members intended to endorse those views by voting in favour of the impugned decision, having been convened for a special session at the urgent request of the United States. However, the decision itself merely indicates that the Conference is determined "to work for the preservation and effective functioning of the Organization and the Convention, which are put in jeopardy by the lack of confidence in the present Director-General of the Technical Secretariat". Thus, the motion that was voted on was a genuine no-confidence motion, with no other basis than the threat which the complainant's conduct and management posed to the Organisation.

16. In accordance with the established case law of all international administrative tribunals, the Tribunal reaffirms that the independence of international civil servants is an essential guarantee, not only for the civil servants themselves, but also for the proper functioning of international organisations. In the case of heads of organisations, that independence is protected, inter alia, by the fact that they are appointed for a limited term of office. To concede that the authority in which the power of appointment is vested - in this case the Conference of the States Parties of the Organisation - may terminate that appointment in its unfettered discretion, would constitute an unacceptable violation of the principles on which international organisations' activities are founded (and which are in fact recalled in Article VIII of the Convention, in paragraphs 46 and 47), by rendering officials vulnerable to pressures and to political change. The possibility that a measure of the kind taken against the complainant may, exceptionally, be justified in cases of grave misconduct cannot be excluded, but such a measure, being punitive in nature, could only be taken in full compliance with the principle of due process, following a procedure enabling the individual concerned to defend his or her case effectively before an independent and impartial body. In this instance, the complainant had no procedural guarantee, and given the circumstances of his case, he has good grounds for asserting that the premature termination of his appointment violated the terms of his contract of employment and contravened the general principles of the law of the international civil service.

17. Consequently, the impugned decision must be set aside and the complainant's further pleas need not be examined by the Tribunal. The complainant, who does not seek reinstatement, is entitled to compensation in respect of the injury caused by his unlawful dismissal. The Tribunal considers that his material injury may be properly assessed by determining the amount he would have received in salaries and emoluments (excluding representation allowance) between the date of his dismissal and 12 May 2005, subject to the deduction of any sums paid to him in connection with the cessation of his functions. As regards compensation for the moral injury undoubtedly suffered by the complainant, the Tribunal shall award him 50,000 euros in moral damages, which he shall be free to dispose of as he sees fit.

18. Since he succeeds, the complainant is entitled to an award of costs, which the Tribunal sets at 5,000 euros.

For the above reasons,

1. The decision taken by the Conference of the States Parties of the OPCW on 22 April 2002 is set aside.

2. The OPCW shall pay the complainant material damages calculated as per consideration 17 of the present judgment.

3. The Organisation shall also pay him 50,000 euros in moral damages.

4. It shall pay him 5,000 euros in costs.

In witness of this judgment, adopted on 15 May 2003, Mr Michel Gentot, President of the Tribunal, Mr James K. Hugessen, Vice-President, and Mrs Mary G. Gaudron, Judge, sign below, as do I, Catherine Comtet, Registrar.

Delivered in public in Geneva on 16 July 2003.

Michel Gentot

James K. Hugessen

Mary G. Gaudron

Catherine Comtet

1. Staff Rule 11.3.01 reads as follows:

"(a) Staff members shall have the right to appeal to the Administrative Tribunal of the International Labour Organisation, in accordance with the provisions of the Statute of that Tribunal, against administrative decisions and disciplinary actions taken, after reference to the Appeals Council.

(b) A staff member may, in agreement with the Director-General, waive the jurisdiction of the Appeals Council and appeal directly to the Administrative Tribunal of the International Labour Organisation, in accordance with the provisions of the Statute of that Tribunal."

__________